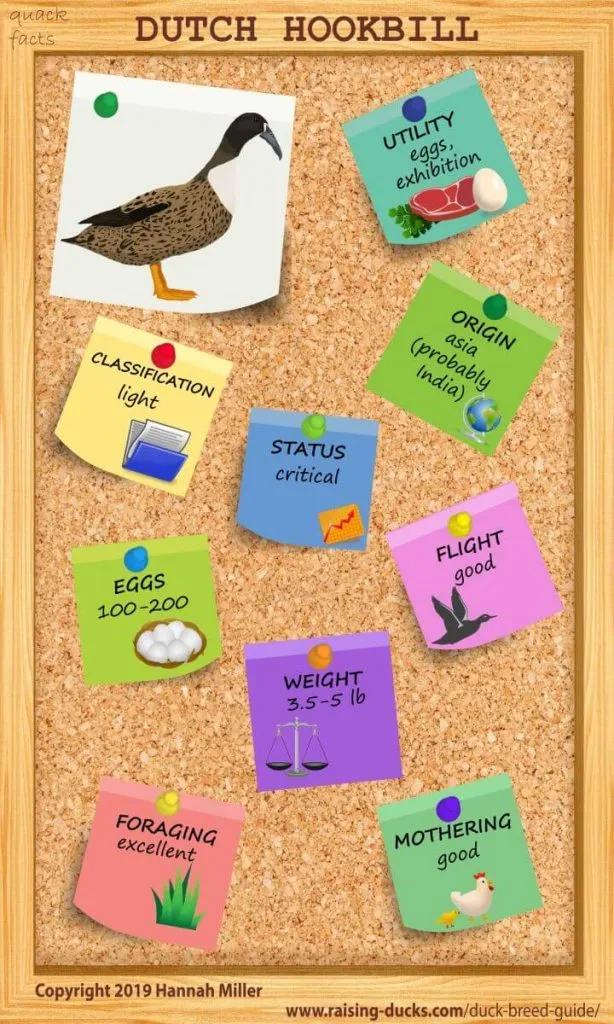

The most striking feature of the extremely rare Dutch Hookbill duck is, of course, its curved “Roman-nosed” bill. No other duck breed has a bill like this.

They’re a light breed, weighing only 3.5-5 pounds. They’re primarily used for eggs or exhibition. They lay 100-200 white, blue, or green eggs per year. They fly well. They’re also usually fairly good mothers and broodies. They’re easy to keep, docile, friendly, and get along well with other ducks.

Featured image (top) used with permission from avicoliornamentali.it.

They’re supreme foragers, and many are able to find all the food that they need, because that was what they were expected to do when they were first developed. Many consider them to be the best foragers of all duck breeds. Thus, aside from their unique appearance, their self-sufficiency is one of their most prominent traits.

Photo used with permission from avicoliornamentali.it.

There are several color varieties of the Dutch Hookbill. Most birds are white, dusky Mallard, or white-bibbed dusky Mallard. Aleutian, snowy, golden, and gray also exist, but are extremely rare, and it has been speculated that there used to be many more colors that are now completely extinct.

View this post on Instagram

Dutch Hookbills are Europe’s oldest duck breed, having been mentioned in writings in Holland as early as 1676. Interestingly, Charles Darwin was said to have a flock of Dutch Hookbills on his pond. They were popular as egg-layers in Holland for a long time, and were raised in canals, where they foraged for themselves. One theory as to their origination (there are various theories; some state that the Dutch Hookbill originated in India from Indian Runners) is that they were bred with curved bills so that hunters could differentiate between the domestic ducks and wild ones.

However, their popularity declined, and by 1980, they were all but extinct, due to lack of demand for duck eggs and the pollution of the waterways and canals where they lived. At this point, a conservation breeding program was started with the last 15 birds that were found. Dave Holderread imported them to the United States in 2000. Since then, their numbers have grown, but not nearly enough. Today, they’re still extremely rare and are listed as “Critical” by the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy. They were standardized by the British Waterfowl Standards in 1997, but aren’t yet in the American Standard of Perfection. Worldwide, there are estimated to be about 400 birds.

PHOTO AND VIDEO GALLERY

Here’s an interesting video about a man trying to start a small flock of breeding-quality Dutch Hookbills.

Photo used with permission from avicoliornamentali.it.

Photo used with permission from avicoliornamentali.it.

Photo used with permission from avicoliornamentali.it.

Photo used with permission from avicoliornamentali.it.

Photo used with permission from avicoliornamentali.it.

View this post on Instagram

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published.